It seems that comics have a role to play in saving humanity, at least according to HBO.

In this week’s episode of The Last of Us (“Endure and Survive”) two children come across an old comic book in an abandoned underground shelter. They are delighted, which is honestly a rare emotion in this otherwise grim world.

The Last of Us depicts a world that has been overrun with humans that have either become zombified by mushrooms or have become emotionally zombified by the violence they’ve had to enact in order to survive. The series is based on a video game where the main mechanics appear to be shooting, sneaking around, and resource management. In this world where people are willing to become fascist collaborators for the opportunity to eat a single apple, comics still seem precious. These kids still want to stop and read a comic even though they know that stopping for even a second could mean instant death, or an even more monstrous version of life.

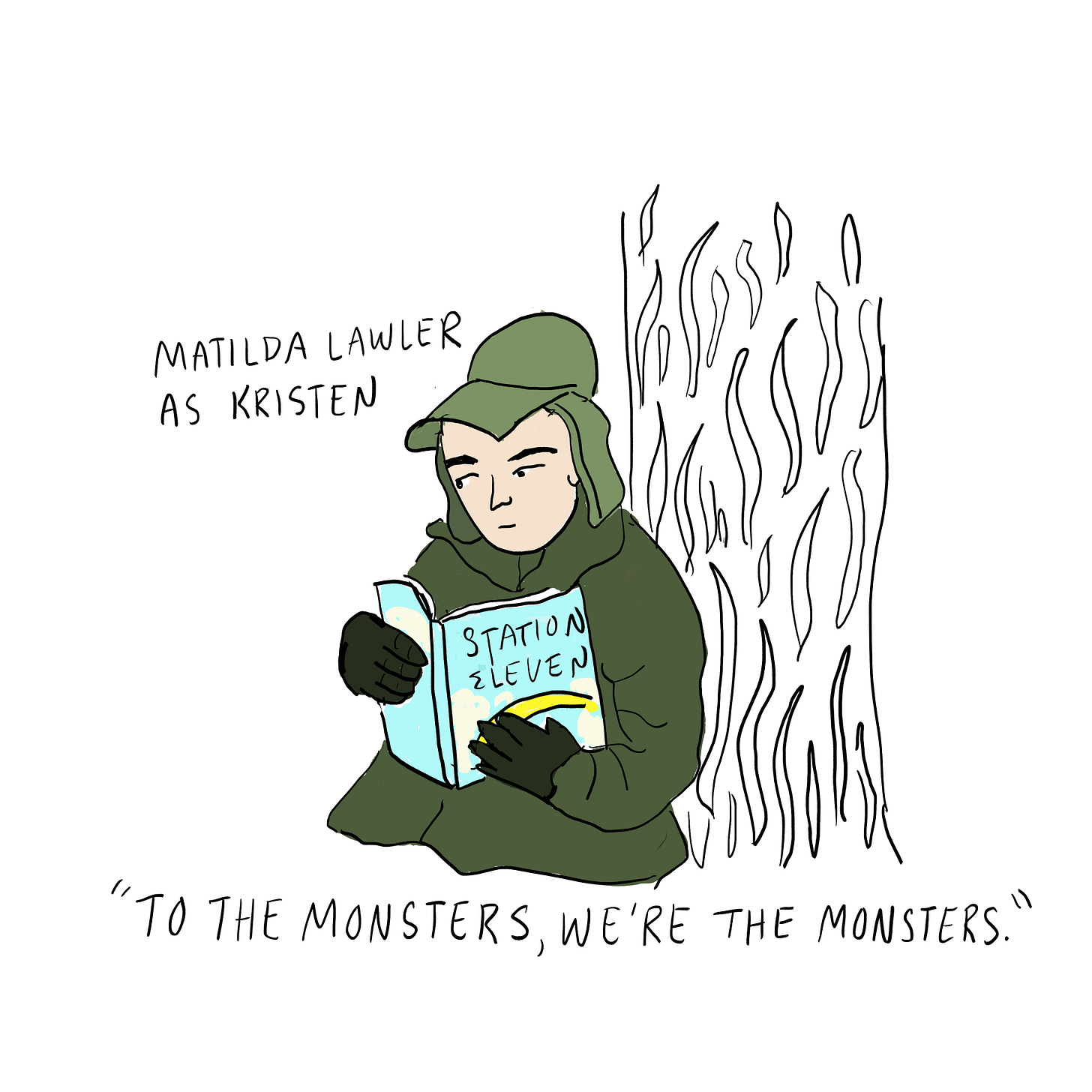

Comics are even more important in Station Eleven, another apocalyptic tv series on HBO about people trying to survive in a post-pandemic hell-scape. Station Eleven is the name of a comic book that takes takes on an almost spiritual significance for each of the characters in unpredictable ways. Station Eleven’s author, Miranda Carroll, is the best kind of cartoonist—she drew the book for herself because she had a story to tell, and worked on it in stolen moments between her day job and annoying husband, with no expectation that anyone would ever see it other than her.

Even though Miranda only ever produced a single copy of her book, this copy managed to circulate and resonate with children of the next world.

It’s not hard to imagine why comics are so captivating in the most dire of circumstances. They are a visual medium that don’t require electricity or fancy equipment to enjoy. Comics can be understood across languages, and honestly, you don’t even need to know how to read in order to enjoy them. Not only that, but comics don’t require huge amounts of capital or teams of people to produce. You can imagine yourself finding a crayon in the ashes, a piece of paper among the rubble, and boom, you have everything you need to make a comic.

For me, this is what inspired me to make comics in the first place, the idea that I could make them by myself with materials I already had access to. I started drawing comics after I got kicked out of a film studies PhD program (a story for another day). I thought about trying to make films or music, but then I would need stuff I couldn’t actually afford, and I would need to work with other people—people who could tell me my work was bullshit at any time. I didn’t need anyone’s permission to draw a comic and no one could tell me my comics weren’t intellectual enough because hey, it’s just a comic, relax.

I don’t have to imagine a zombie apocalypse to see the value of art that can be made in an emergency, and endure, mainly because others might mistake it for a piece of trash.

Thank you as always for reading.

*I tried something a little different with this newsletter. I’d love to hear your thoughts on what you’d like to see from me. Diary comics? Film commentary comics? Stuff about my process? Something else? Comment below.

i want to see it all, but i think creative process is at the top of the list

Like Sydney, I also want to see it all! I really enjoy your comic essays, like the ones you did a few years ago about Tarot on Medium, but I will read whatever you end up doing here.